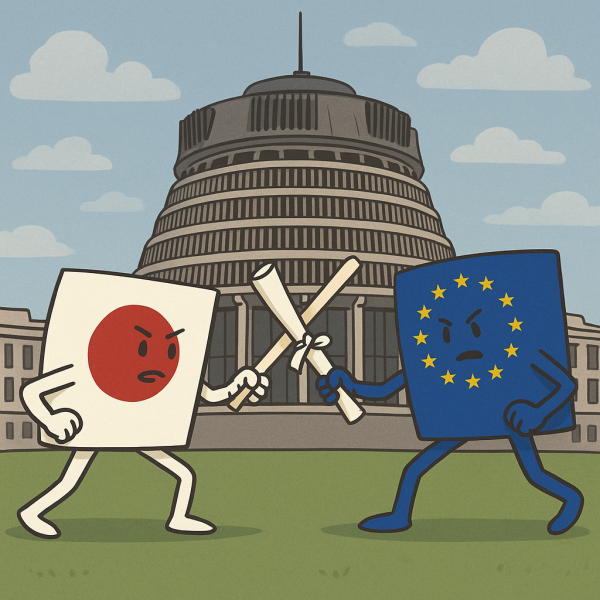

Why Do We Keep Using Europe as the Yard-Stick?

When it comes to vehicle emissions, Wellington’s default setting seems to be “What would Brussels do?” The Euro standards are treated as holy writ, while every other regime—including the one that supplies the bulk of our fleet—must scramble to prove it deserves a seat at the table. That might have passed muster in the 1990s, when EU brands dominated Kiwi showrooms, but it is a curious stance in 2025 when roughly 90 percent of our used‐import pipeline still originates in Japan. Shouldn’t the benchmark reflect the reality of our supply chain?

A Case Study: Japan 2005 vs Euro 5

The current wrangle with NZTA over which slice of Japan’s 2005 regulation is “good enough” for Euro 5 tells the story. For years it seemed that the Rule accepted any Japan 05 code (A through D) as meeting Euro 5 outcomes. Then—coincidentally the moment Euro 5 began applying to used imports—we were told only D-code results would count. No explanation of the harm avoided, no cost-benefit, just a quiet administrative shift that locks thousands of efficient and compliant C-code vehicles out of the market and lumps extra cost onto Kiwi households already battling the price of living.

Dig into the history and you find Japan’s 2005 limits were the toughest in the world at the time, beating even Euro IV on particulate matter and matching Euro V on NOx for heavy-diesel engines (dieselnet.com, dieselnet.com). In other words, we are debating whether a standard that was once ahead of Europe is now somehow “not quite up to scratch”.

Different Standards, Different Aims

Part of the confusion stems from comparing rules that were designed for different driving environments. Japan’s metro-heavy traffic pattern pushes regulators to focus on low-speed pollutants (NOx and hydrocarbons) that choke dense cities like Tokyo and Osaka. European lawmakers, with long stretches of high-speed autobahn, have historically weighted diesel particulates and, later, CO₂. Neither approach is wrong—they simply chase the outcomes each society cares about most.

If our policy objective is minimising health-damaging tail-pipe toxins on New Zealand’s urban roads, a Japanese benchmark arguably makes more sense. If the priority is pure carbon reduction, then by all means line up the grams-per-kilometre and pick the toughest rule that is economically workable. The point is: start with the outcome, not with the European directive pages.

The CO₂ Myth

We also hear that European rules are “more ambitious” on carbon. Up to a point. Japan has run a “Top‐Runner” fuel-efficiency programme since 1999, forcing every model year to beat the performance of the best vehicle in its class. The next milestone, in force for model year 2030, lifts the fleet’s target to 25.4 km per litre (about 3.9 L/100 km) (theicct.org). That translates to roughly 95 g CO₂/km—only a hair above the EU’s own 2030 goal once you normalise the test cycles. Analyses comparing long-range ambition put Europe and Japan neck-and-neck, with both aiming for real‐world fuel figures north of 70 mpg by the end of the decade (aceee.org).

In short: Japan is not the laggard some assume. If anything, its weight-based system does a better job of avoiding perverse outcomes (think giant SUVs magically “complying” because the weighting curve lets them off).

The Cost of Euro-First Thinking

Choosing a European standard as the default imposes real costs on New Zealand:

- Supply-chain distortion – Japanese exporters now tailor shipments to meet an EU benchmark that applies to virtually none of their domestic customers, limiting the pool of cars available for Kiwi buyers.

- Vehicle inflation – When you narrow eligibility to a niche sub-set (e.g., D-code only), you bid up prices on the limited stock that qualifies. That flows straight through to retail pricing at a time when household budgets are already stretched.

- Regulatory churn – Importers spend months chasing equivalency charts, translating Japanese test data into European codes, and paying consultants to fill the paper trail—time and money that could be spent on genuine decarbonisation projects.

None of this makes the air cleaner or the climate cooler. It simply privileges one foreign test cycle over another.

A Smarter Path: Outcome-First Regulation

So what would make sense?

- Define the harm horizon. Decide (publicly) whether the priority is tonne-kilometres of CO₂ avoided, grams of NOx at the kerbside, or some balanced basket.

- Score competing standards. Map Japanese, European, US and emerging Chinese limits against those outcomes. A spreadsheet can do this in an afternoon; no need for a three-year working group.

- Adopt all standards that meet the goal. If Euro 5, Japan 05-C, and US Tier 2 Bin 5 all deliver the same real-world result, write them all into the Rule. Let importers source the cleanest, cheapest vehicles they can find, irrespective of which testing lab stamped the certificate.

- Update the matrix annually. As the big economies ratchet their rules, we toggle the table, not rewrite the Act.

Regulation done this way is technology-neutral, origin-neutral and focused on the environmental outcome taxpayers actually care about.

Time to Break the Habit

Our current Euro-first mindset is a relic of an earlier market mix. It no longer reflects where New Zealanders’ cars are built, nor does it necessarily deliver the best bang for our decarbonisation buck. The Japan 2005 saga is a flashing warning light: if we keep treating European law as the gold standard by default, we will keep tripping over misalignments, supply squeezes and unintended costs.

Let’s set the destination first—clean air and low carbon—and then judge every standard, European, Japanese or otherwise, on how quickly and cheaply it gets us there. Anything else is policy inertia dressed up as best practice.